Executive summary

I Recovering irregular expenditure from beneficiaries of EU funds is a key element of the EU’s internal control systems, as it should protect the EU’s financial interests and deter recipients from future irregular activities. The Commission reported €14 billion of irregular expenditure in 2014-2022.

II The purpose of this audit was to assess whether the Commission’s systems for managing and monitoring irregular expenditure incurred by beneficiaries of EU funds are effective. The Commission’s responsibilities in this area vary depending on the type of management mode and the policy area of the EU budget. Under shared management, the Commission delegates the responsibility for the recording and recovery of irregular expenditure to member states, but retains ultimate responsibility. With this audit, we aim to help increase protection of the EU’s financial interests and develop effective systems for recovering irregular expenditure from recipients of EU funds.

III We concluded that the Commission’s systems for managing and monitoring irregular expenditure incurred by beneficiaries of EU funds are partially effective.

IV Under direct and indirect management, the Commission ensures the accurate and prompt recording of irregular expenditure, but takes too long to recover it. The Commission does not follow up potentially systemic irregular expenditure for external actions in the same way as it does for internal policies. Debts that have been written off usually involve debtors that were financially weak, or that were located in countries where the Commission could not enforce debts through the local courts.

V Under shared management, member states have primary responsibility for recording and recovering irregular expenditure, and the Commission monitors their systems in agriculture. We observed that recovery rates at beneficiary level for the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) are generally lower than those for direct and indirect management and have not improved since 2006, and that there are significant differences in recovery and write-off rates between member states. Furthermore, the incentive that the Commission introduced in 2006 for member states to recover debts faster was not retained in the CAP 2023-2027. In these circumstances, the Commission’s monitoring might not be sufficient on its own to ensure the effective performance of member state recovery systems. In cohesion, the EU budget is protected by member states withdrawing irregular amounts from certified expenditure. The Commission does not follow up the extent to which member states recover the withdrawn irregular expenditure from beneficiaries. The recovery of irregular amounts is a key tool to deter beneficiaries from committing further irregularities and to minimise the reputational risks for the EU.

VI Furthermore, the usefulness of the information that the Commission provides on irregular expenditure and subsequent corrective measures is limited because it is not always complete and consistently presented.

VII We recommend that the Commission should:

- examine the financial impact of systemic irregularities in the area of external actions;

- improve the planning of audit work in the area of external actions to reduce the time taken to establish irregular expenditure;

- assess the need for additional incentives for member states to improve the rates of recovery of irregular expenditure in agriculture; and

- provide complete information on established irregular expenditure and corrective measures taken.

Introduction

Recovering irregular expenditure from recipients of EU funds

01 According to Article 325(1) of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU), the EU and member states share responsibility for protecting the Union's financial interests from fraud and any other irregularity. An irregularity is defined as any infringement of a provision of a contract or of an EU regulation resulting from an act or an omission, which causes, or might cause, a loss to the EU budget1. When the irregularity affects expenditure recorded in the EU budget, it is known as irregular expenditure.

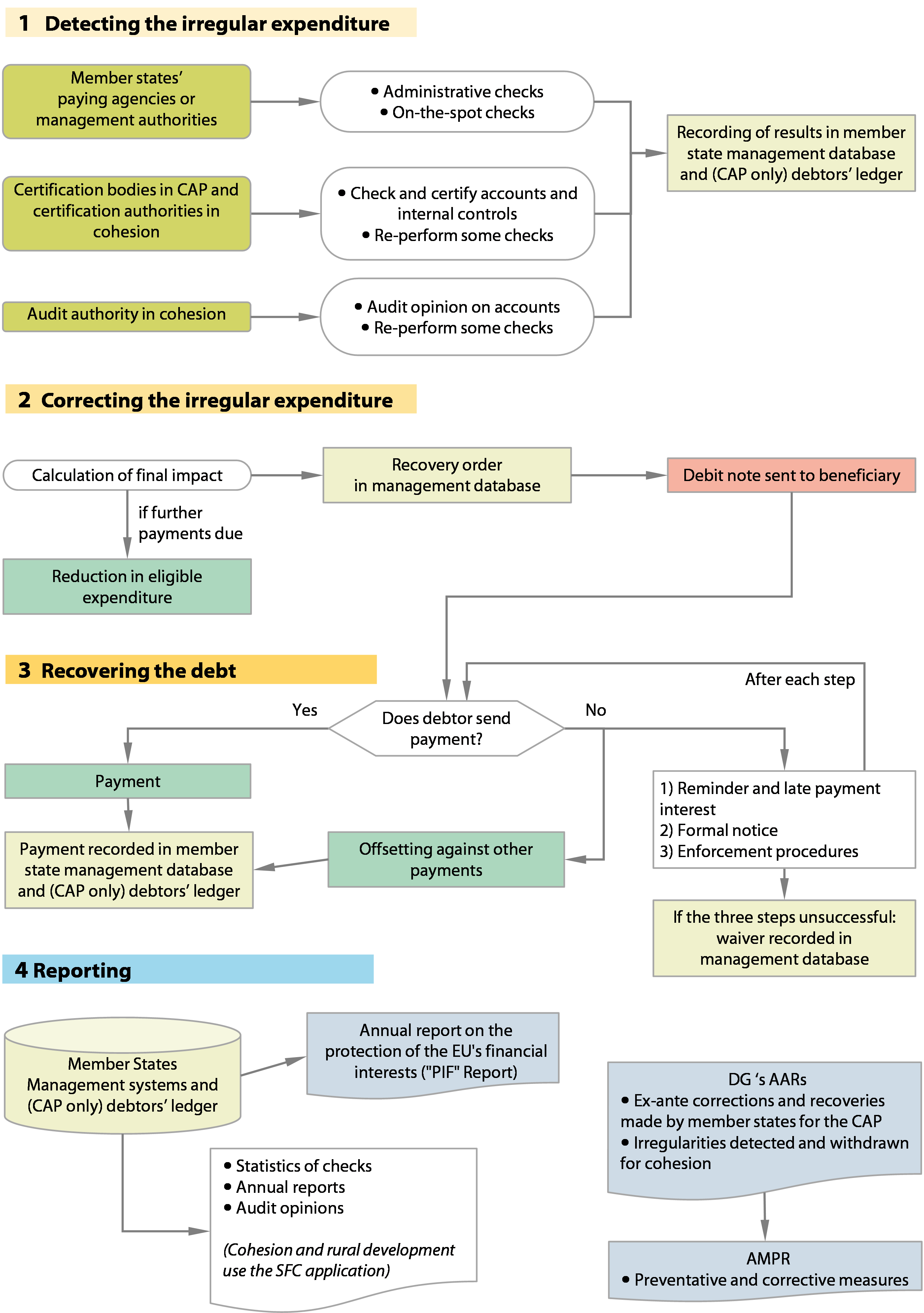

02 The Commission and member states must put internal controls in place to protect the EU budget from irregular expenditure2. They carry out ex ante checks before the authorisation and payment of financial operations to prevent irregular expenditure from being accepted, and ex post checks after the operations have been authorised and paid in order to detect and correct irregular expenditure if prevention fails3. Figure 1 illustrates the Commission’s multiannual control cycle for preventing, detecting and correcting irregular expenditure.

Figure 1 – The Commission´s multiannual control cycle for preventing, detecting and correcting irregular expenditure

Source: ECA based on Commission’s 2022 Annual Management and Performance Report, Volume II, Annex 2, p. 51.

03 When ex post checks detect irregular expenditure, there are two main measures for protecting the EU’s financial interests:

- direct recovery from the beneficiary that committed the irregularity4; or

- a financial correction imposed on the member state that financed the irregular expenditure in order to compensate for it5.

04 For the purpose of this audit, “recovery†means a measure to protect the EU’s financial interests by requesting the refund of some or all of the amounts paid to an implementing organisation or beneficiary of an EU-supported project or programme that has not adhered to EU funding requirements. Implementing organisations are beneficiaries of EU funds that provide goods and/or services to final recipients and are liable if they do not fulfil the conditions of their contracts or agreements.

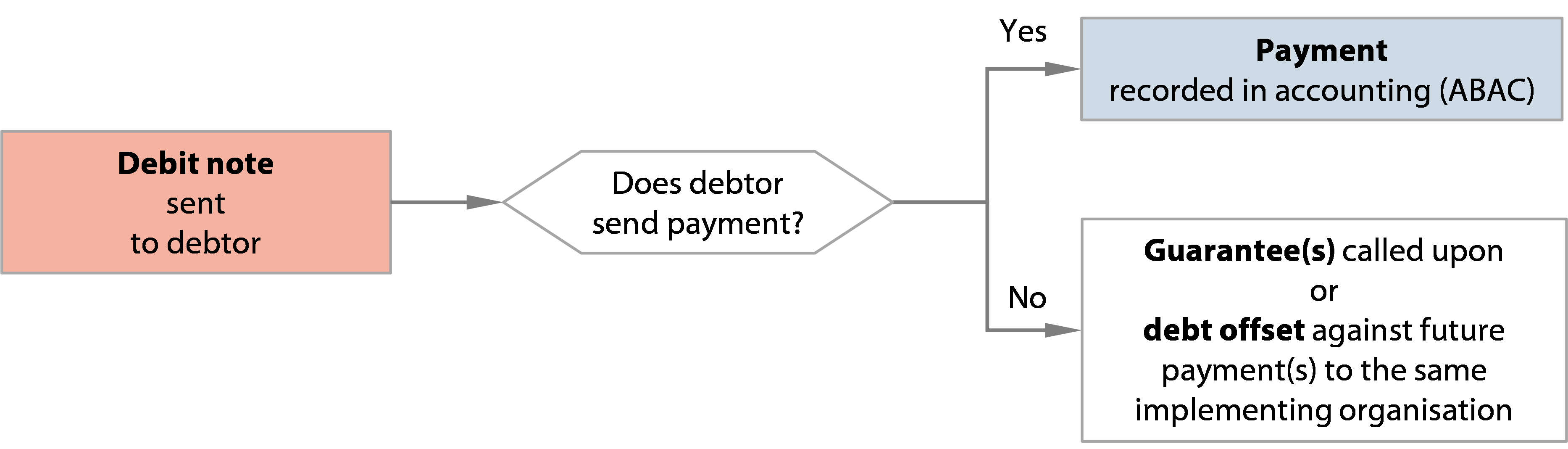

05 The organisations that are responsible for managing the EU-funded programme or project (the Commission under direct management, partner organisations or other authorities inside and outside the EU under indirect management, and national authorities under shared management) may make recoveries from beneficiaries in two ways, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 – Recovering amounts owed

Source: ECA.

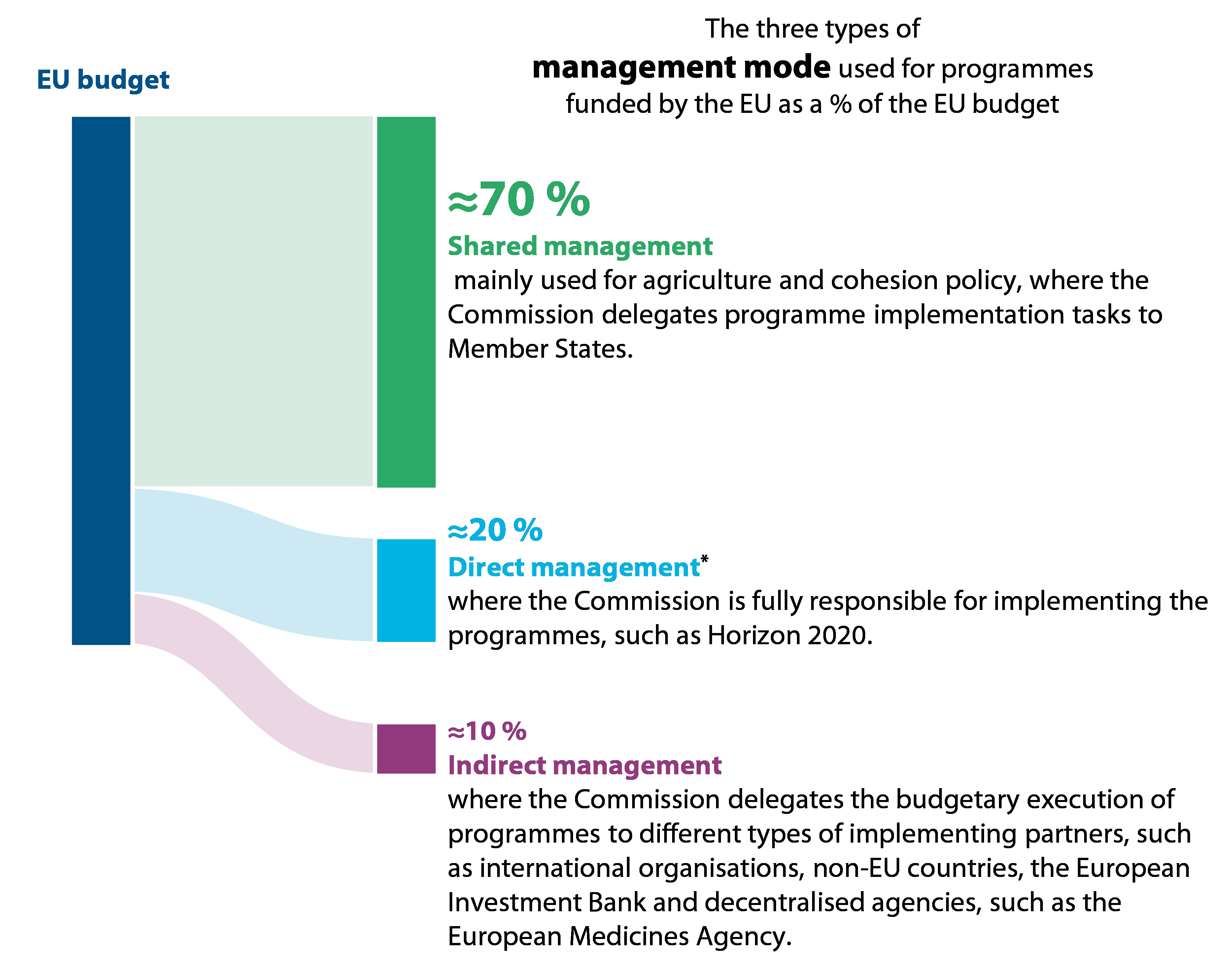

06 The procedures for recovering irregular expenditure from beneficiaries depend on the type of management and the policy area of the EU budget. A more detailed explanation of the control and recovery procedures for each main policy area is provided in Annex I to Annex III. The three types of management used for programmes funded by the EU are shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3 – Management modes

*Direct management excludes the funding of the Recovery and Resilience Facility.

Source: ECA based on Article 62 of the Financial Regulation and https://commission.europa.eu/funding-tenders/find-funding/funding-management-mode_en.

Systems for recording irregular expenditure and amounts to be recovered

07 The Commission records irregular expenditure that it detects or that is reported to it for direct and indirect management in local audit management databases. These include the Audit Module for External Actions and AUDEX for the research Directorates-General (DGs) in internal policies.

08 Once the impact of the irregular expenditure is determined, the Commission uses the 'Recovery Context' function in its ABAC accounting system to record all amounts to be recovered. Recovery Context mainly applies to direct and indirect management policy areas because under shared management member states are responsible for making recoveries from beneficiaries, recording them in their national debtor’s ledgers and, where required, reporting the data to the Commission on a regular basis.

09 EU law requires member states and EU candidate countries to use the Irregularity Management System, managed by the European Anti-Fraud Office (OLAF) on behalf of the Commission, to record cases of irregular expenditure (including suspected and established fraud) that they have detected and that involve more than €10 000 of EU funds6. This is intended for risk analysis, not for following up recoveries.

Roles and responsibilities

The Commission, national authorities and implementing partners

10 Under direct management, Commission DGs managing EU-funded programmes or grants are responsible for performing checks and recovering irregular expenditure that has been detected. DGÂ BUDG provides guidance and support during the recovery process.

11 Under indirect management, implementing partners should ensure a level of protection of EU funds equivalent to that of the Commission under the direct management arrangement. They are responsible for performing checks and recovering irregular expenditure from beneficiaries. If verifications of financial reports submitted to the Commission detect irregular expenditure, the Commission requests that implementing partners reimburse the EU funds. If applicable, implementing partners in turn request that final beneficiaries repay the funds to them.

12 Under shared management, member states are responsible for the recording and recovery of irregular expenditure, while the Commission has the ultimate responsibility for assurance on the system put in place by member states for the management of the funds. Member state authorities have primary responsibility for carrying out checks and for recovering irregular expenditure directly from beneficiaries. Each year, they report the results of their checks on the use of EU funds to the Commission. The Commission carries out audits to assess the effectiveness of member states’ systems and may impose financial corrections if it detects weaknesses that may impact the EU budget.

European Anti-Fraud Office - OLAF

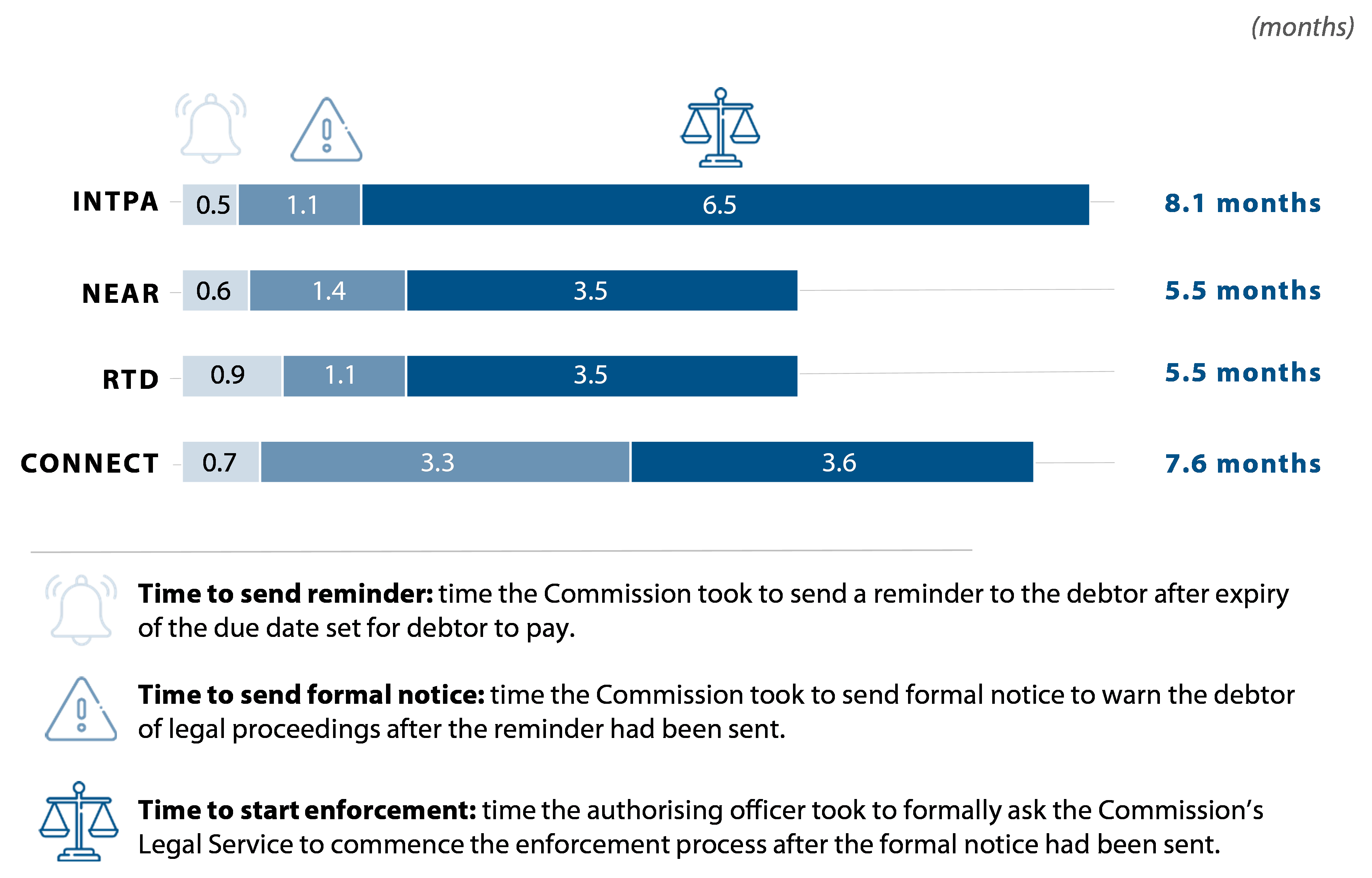

13 OLAF investigates suspected cases of fraudulent and non-fraudulent irregular expenditure, and then sends its investigation reports to the EU institutions or member state authorities concerned. It may also recommend what disciplinary, administrative, financial or legal action they should take. In its financial recommendations, OLAF invites the relevant EU or national authorities to recover EU funds that were affected by fraudulent or non-fraudulent irregular expenditure.

European Public Prosecutor’s Office - EPPO

14 EPPO, which was established in 2017, is an independent EU body with powers to investigate, prosecute and bring to judgment crimes against the EU budget, such as fraud, corruption or serious cross-border VAT fraud, as defined in the PIF Directive and Council Regulation (EU) 2017/1939. It started work in June 2021. In line with the cooperation agreement signed by the Commission and EPPO, when EPPO opens an investigation based on information submitted by the Commission, it will inform the Commission and provide it with sufficient information in order to take corrective measures, such as the recovery of unduly paid funds.

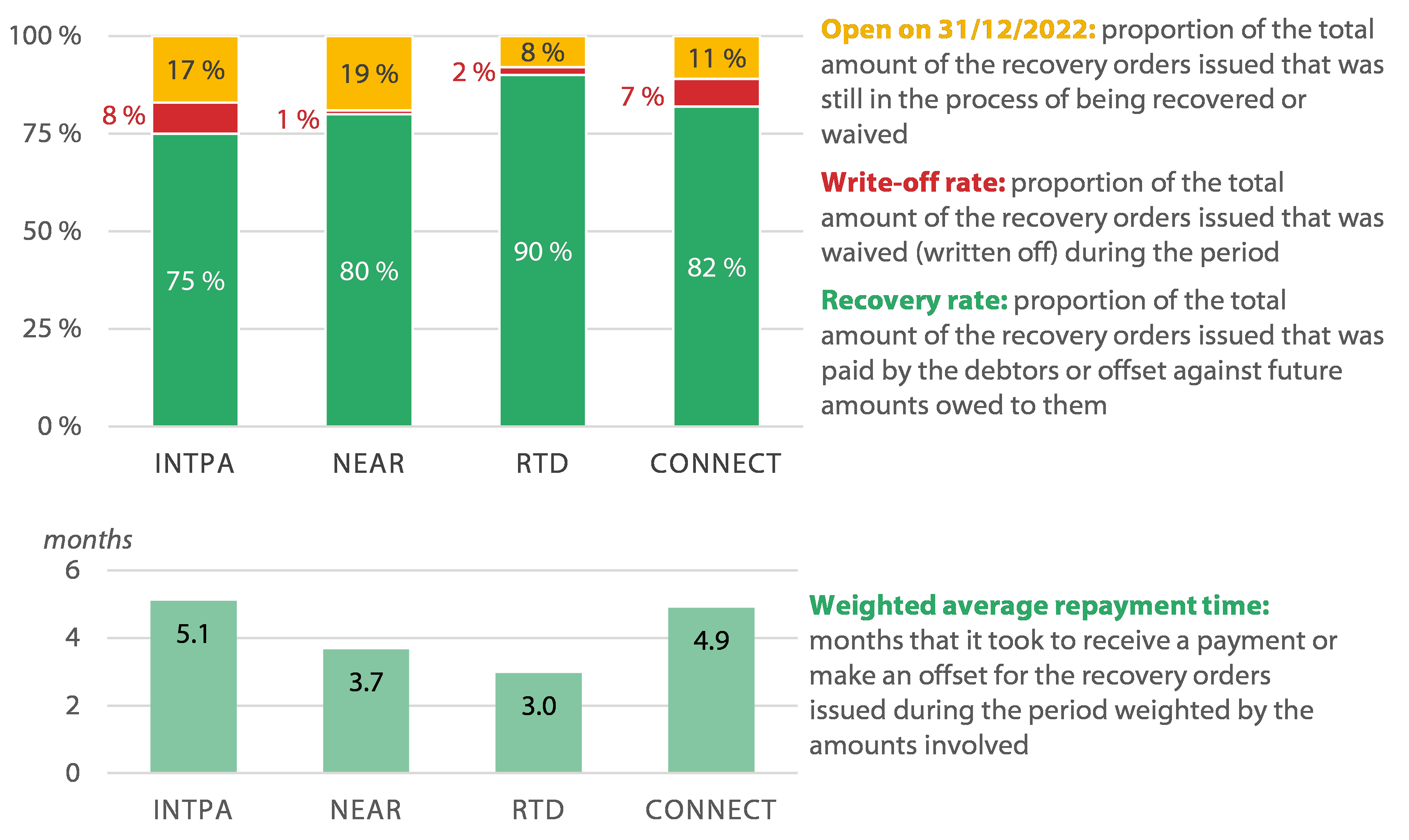

Published information on irregular expenditure and recoveries

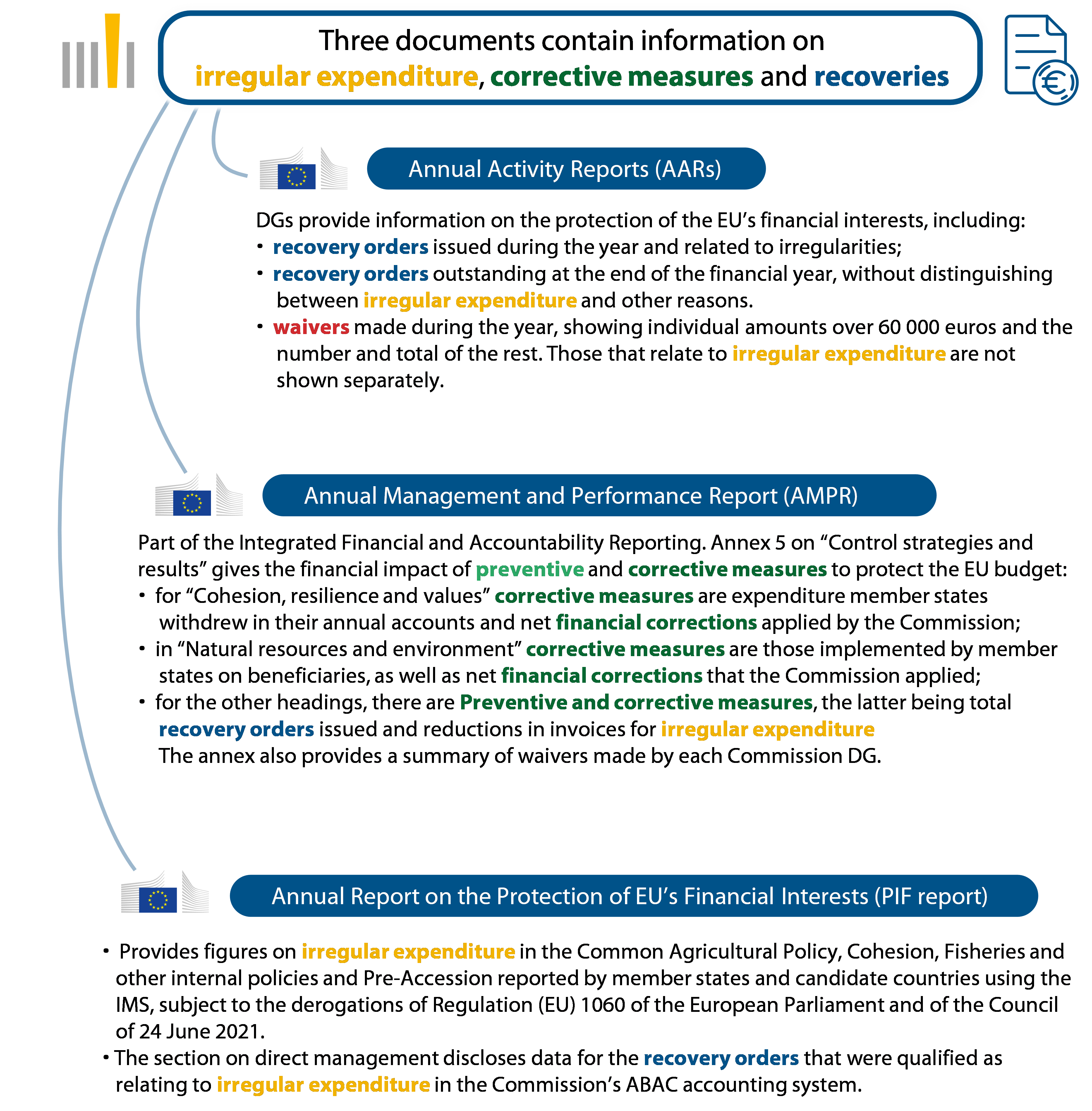

15 The Commission’s published documents that contain information on irregular expenditure, corrective measures and recoveries of irregular expenditure are shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4 – Commission’s published documents on irregular expenditure and recoveries

Source: ECA based on AAR, AMPR and PIF reports published by the Commission.

16 Section 5.4 of Annex 5 of the 2022 AMPR provides the figures for recoveries from beneficiaries of irregular expenditure that was detected and reimbursed, or that is to be reimbursed to the EU budget; see Table 1.

Table 1 – AMPR reporting of recovery orders issued for irregular expenditure in 2021 and 2022 (million euros)

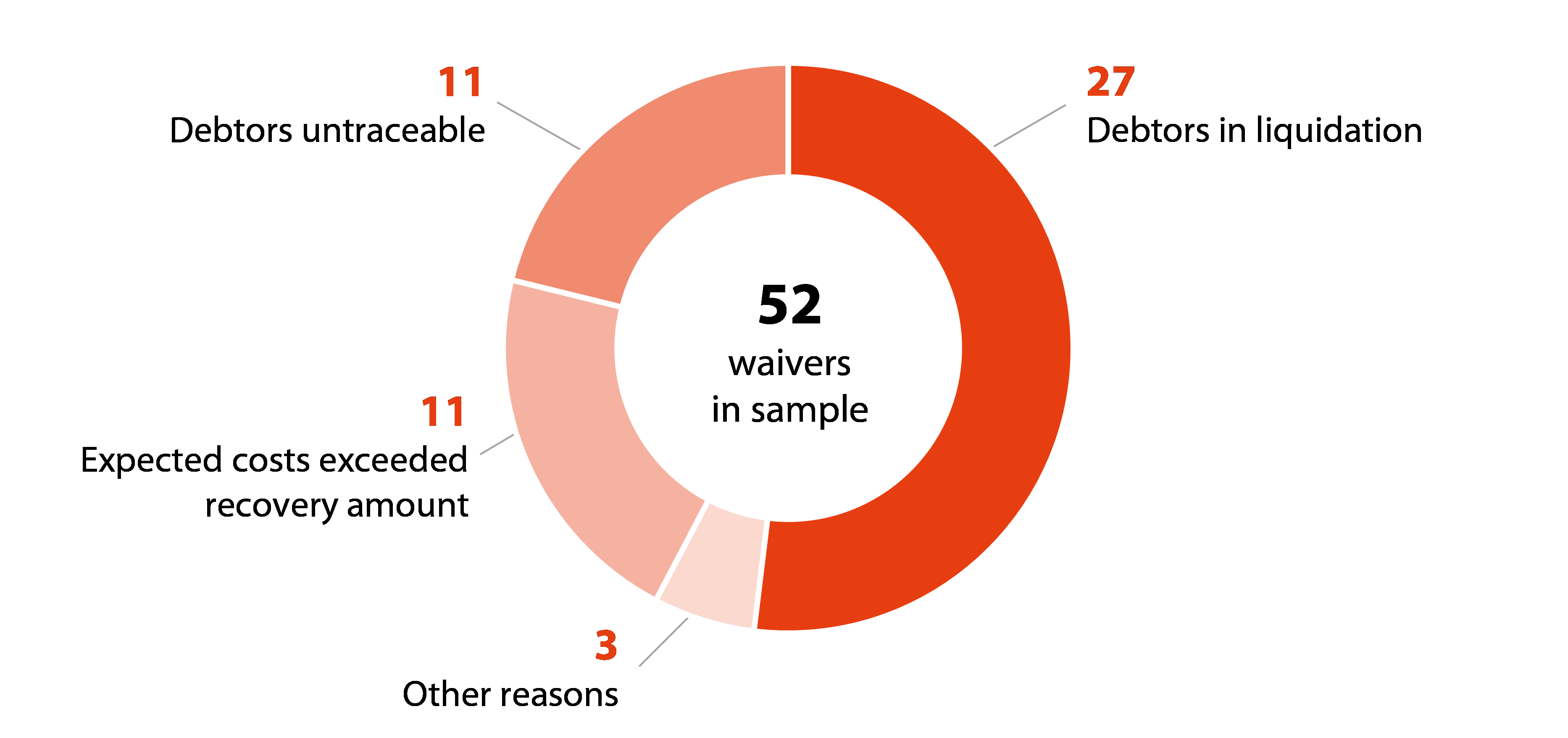

MFF heading | Recoveries 2021 | Recoveries 2022 |

|---|---|---|

Single market, innovation and digital | 19 | 27 |

Cohesion, resilience and value | Not applicable * | Not applicable * |

Natural resources and environment | 191 *, ** | 220 *, ** |

Migration and border management | 1 * | 1 * |

Security and defence | 0 | 0 |

Neighbourhood and the world | 21 | 16 |

European public administration | 0 | 1 |

*Excludes corrections applied by the Commission to member states. In cohesion, expenditure directly withdrawn by member states are reported in the AAR and in the AMPR.

**This amount was reimbursed to the EU budget in addition to €118 million (€244 million in 2021) that was re-used by member states.

Source: ECA based on preventive and corrective measures in section 5.4 of the 2022 and 2021 AMPRs.

17 The Commission also provides a summary in the AMPR of the amounts waived by each DG7. In 2023, the Commission reported that in 2022 it had waived debts totalling €40 million8 (€31 million in 2021). The figures are for waivers of all types of debts, not just recoveries of irregular expenditure.

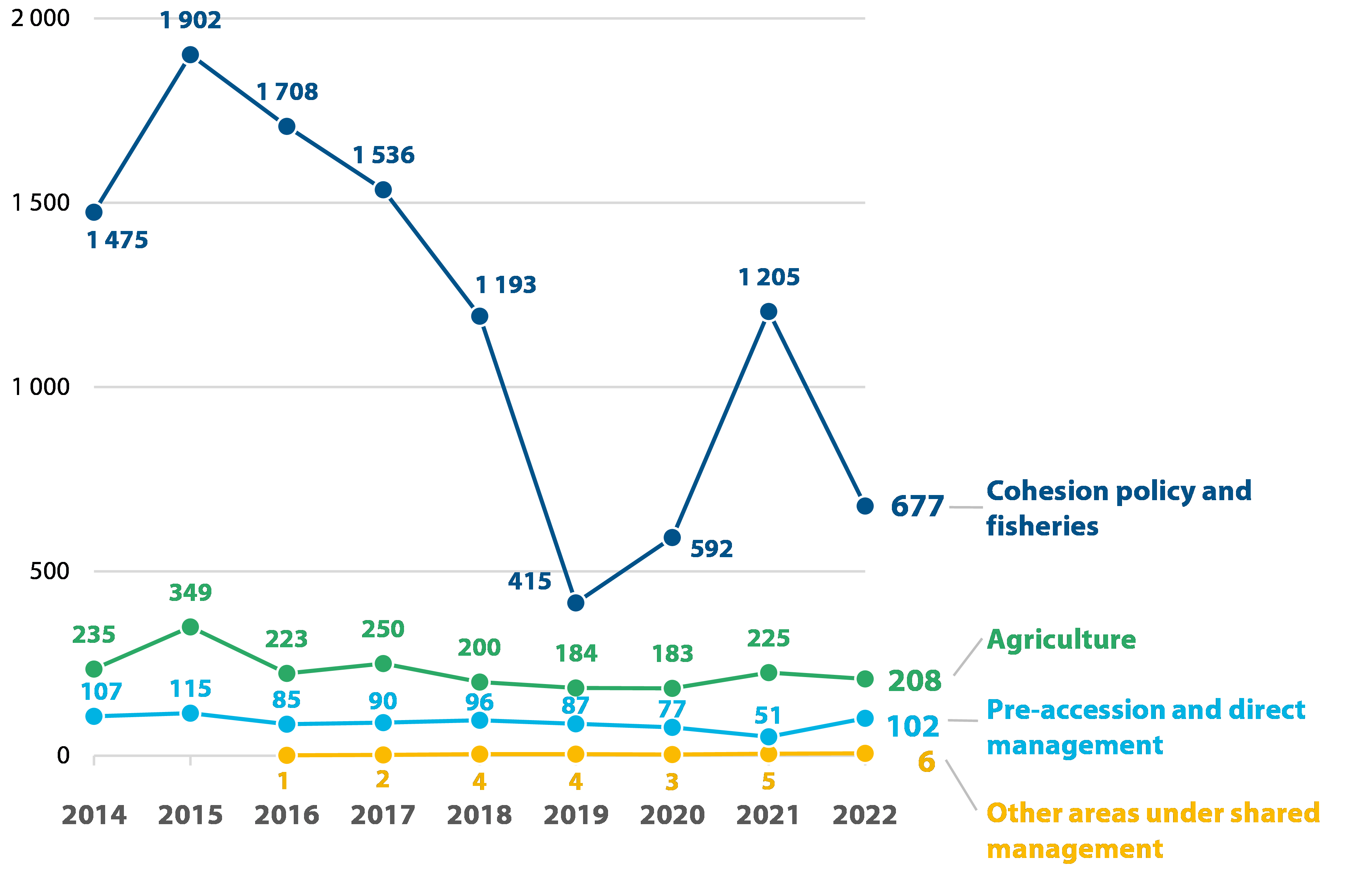

18 The total amount of irregular expenditure (fraudulent and non-fraudulent) reported in the PIF reports for the EU budget for 2014-2022 was €14 billion. This includes €10.7 billion for cohesion policy and fisheries, where member states must withdraw irregular expenditure as soon as it is detected, so that it does not affect the EU budget. The breakdown by policy area and by year is shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5 – Irregular expenditure reported in 2014-2022 (million euros)

Source: ECA based on data provided by OLAF.

Audit scope and approach

19 The purpose of this audit was to assess whether the Commission’s systems for managing the recovery of irregular expenditure incurred by beneficiaries of EU funds are effective. We covered EU programmes between 2014 and 2021 with the most significant recoveries under direct, indirect and shared management: internal policies, external actions, and cohesion policy and agriculture respectively.

20 With regards to direct and indirect management, where the Commission is responsible for identifying and recording irregular expenditure, and then recovering the funds, we assessed the effectiveness of the Commission’s systems. This was the main focus of the audit. In the area of shared management, the regulations entrust the member states with responsibility for recovering irregularly spent funds, but the Commission has ultimate responsibility for assurance. Since the scope of our audit focused on the Commission, for this area we assessed whether the Commission’s monitoring ensures that member state systems are effective. For all management modes, we also assessed whether the Commission reports appropriately on irregular expenditure and recoveries in its key published accountability documents.

21 The audit work involved DG BUDG, as well as the most significant DGs in terms of recovery amounts in their 2021 AARs (DGs CONNECT and RTD for internal polices, and DGs INTPA and NEAR for external actions) and the leading shared management DGs (REGIO and EMPL for cohesion policy and AGRI for agriculture).

22 The audit did not cover:

- recoveries of unused funds, the vast majority of which relate to pre-financing (which is not expenditure), with the funds being recovered because they are not used (rather than due to irregular expenditure);

- the financial corrections that the Commission applies to member states in agriculture and cohesion, or withdrawals made by member state authorities, because we addressed this issue in previous special reports9;

- the member states’ systems for recovering irregular expenditure in cohesion and rural development programmes, as we focused on the Commission’s checks to monitor the effectiveness of member states’ recovery systems; and

- the Recovery and Resilience Facility because we have already published a special report on the design of the Commission’s systems to protect the EU’s financial interests10 and we plan to publish a special report on member state RRF control systems in 2024.

23 The audit combined evidence from a range of sources, including:

- a review of the systems used to detect, record and then recover irregular expenditure from beneficiaries;

- an analysis of data from the Commission’s ABAC management database of recoveries made, outstanding and written off between 2014 and 2022 in order to compare the Commission’s performance in different areas;

- reviews of the follow up of a sample of 144Â reports of audits and verifications of financial reports on EU-funded expenditure (based on the size of the amounts checked and including different types of checks), a sample of 75Â recovery orders out of the 858 that were open at the end of 2021 (based on the age and size of amounts) and a sample of 52Â waivers of recovery orders out of the 113 issued during 2021 (based on size) for the four DGs selected for direct and indirect management. Whenever possible, OLAF and ECA cases were included in the samples; and

- an examination of the information that the Commission published on irregular expenditure and recoveries in 2022 and 2023 (paragraphs 15-18), including reconciliations with the sources of data used, the aim being to assess whether it was complete and consistent.

24 Our aim with this report is to help increase protection of the EU’s financial interests and develop effective systems for recovering irregular expenditure from beneficiaries of EU funds.

Observations

The Commission records irregular expenditure under direct and indirect management accurately and promptly, but there are long delays in the recovery process

The Commission records irregular expenditure accurately and promptly

25 We would expect the Commission’s systems under direct and indirect management to ensure correct and timely recording of irregular expenditure in the relevant management databases so that corrective measures can be taken as soon as possible. Despite direct and indirect management setting and pursuing different objectives, the procedures for recording and recovering irregular expenditure are similar.

26 The operational DGs for Research and Innovation in the internal policies’ budgetary area, which include DGs CONNECT and RTD that we selected for this audit, have set up a Common Audit Service (CAS) to select the financial statements of directly or indirectly managed projects to be audited. CAS carries out the ex post financial audits with its own staff or hires private audit firms using a framework contract to carry out the financial audits which are monitored by a CAS representative. CAS and the hired auditors discuss the main findings with implementing organisations during an adversarial procedure, after which the details of the irregular expenditure that has been detected, including irregular expenditure of a systemic and/or recurrent nature, are automatically and immediately transferred from the audit database to the management database. CAS also analyses other financial statements submitted by the same implementing organisations that may also be affected by the same systemic irregular expenditure. The operational DGs concerned can then formally carry out a further short adversarial procedure notifying the implementing organisations of the expenditure that has been rejected.

27 The operational DGs and EU delegations in the external actions budgetary area, which include DGs INTPA and NEAR that we selected for this audit, use a framework contract agreement to hire private audit firms to carry out audits or verifications of expenditure for directly and indirectly managed operations. Audit Task Managers are responsible for monitoring their progress, and for liaising between the implementing organisations and the hired auditors until they have submitted their reports to the Commission.

28 Our checks on the sample of 144 reports of audits and verifications of directly and indirectly managed operations showed that the Commission correctly recorded the irregular expenditure in its management databases within days of receiving the auditors’ reports.

The Commission does not examine potentially systemic irregular expenditure for external actions in the same way as it does for internal policies

29 We would expect amounts recorded as irregular to reflect their full impact. Irregular expenditure of a systemic nature requires further checks to establish its impact.

30 We observed that when potentially systemic irregular expenditure is detected in external actions, the hired auditors are not required to extend the samples of transactions checked. Also, the Commission does not carry out any additional checks of its own on the audited expenditure or on other EU-funded expenditure involving the same implementing organisations.

31 The Commission and the United Nations have established a Financial and Administrative Framework Agreement to work together. The Common Understanding on the use of the terms of reference for expenditure verifications limits the sizes of the samples that verifiers can select to check the eligibility of an operation that a UN agency has managed with EU funds11. Box 1 provides an illustration of how the existing framework limits the detection of systemic irregular expenditure and its subsequent recovery.

Limitations on systemic irregular expenditure detected

The auditor verified the expenditure declared by a UN agency for a contribution agreement with the EU. The auditor reported that 19.2Â % of the sample selected in line with the FAFA was ineligible and concluded that the errors were pervasive. The auditor could not carry out any further checks to confirm the systemic nature of the irregular expenditure and the Commission only recovered the irregular expenditure that had been found in the limited sample that was checked.

There are long delays in recovering irregular expenditure under direct and indirect management

32 Detecting and recovering irregular expenditure from implementing organisations is a key element of internal control systems, as it serves to deter implementing organisations from future irregular activities. Irregular expenditure should be detected and corrected as soon as possible to increase the likelihood of recovery before implementing organisations go into liquidation or become untraceable.

33 Our review of the sample of audits and verifications carried out on the financial reports submitted to the four DGs showed that the latter had completed their corrective measures in 135 out of 144 cases. To calculate the median time taken by the Commission for the main stages between completing the audited activities and issuing recovery orders that are summarised in Figure 6, we used the data from the cases in our sample.

Figure 6 – Significant delays before the Commission can issue recovery orders, 2020-2021

Note: AUDEX does not contain the data needed to calculate how many days had passed before an audit was requested. The figures for the time needed to complete audits are taken from the whole population because it is not possible to obtain data specific to DGs CONNECT and RTD.

Source: ECA based on Audit module and AUDEX databases, and documentation provided by the Commission.

34 If we add the time taken to request and complete audits, and then to discuss the results before recovery orders are issued, our analysis shows that there are significant delays before implementing organisations are asked to repay irregular expenditure that had been detected during checks of expenditure declarations:

- it took the two research DGs, CONNECT and RTD, typically 14Â months to issue recovery orders from the start of the audits, compared to 23 and 18Â months for INTPA and NEAR;

- DGs INTPA and NEAR also typically spent 6 and 5 months to start the contracting procedure for private audit firms after the end of the period covered by the financial reports to be audited. We were unable to obtain the corresponding times for DGs CONNECT and RTD because this information is not entered in AUDEX, their audit management system.

35 For external actions, although the hired auditors discuss their findings with implementing organisations before submitting their reports to the Commission, the Commission carries out a further full adversarial procedure with the implementing organisations (Annex I). As Figure 6 shows, this takes significantly longer than for the research DGs in the area of internal policies, where the CAS takes part in the adversarial procedures between auditors and implementing organisations, so that the operational DGs only need to carry out a formal adversarial procedure that usually lasts less than a month (paragraph 26).

36 These long delays can undermine the effectiveness of audits and the recovery of irregular expenditure, especially in the case of smaller beneficiaries, which might not always ensure that the necessary supporting evidence is available (see example in Box 2).

Supporting documentation was no longer available and the beneficiaries could not repay any funds received

The auditor of a project managed by a local NGO in Africa reported irregular expenditure in declared expenditure due to a lack of supporting documentation. The implementing organisation stated that the NGO and other small local NGOs that had completed the project activities four years earlier could no longer find the missing documentation, despite legislation requiring all beneficiaries to keep documentation for a period of five years. Some of the NGOs no longer existed and the others could not repay the amount requested by the Commission. At the time of our audit, the Commission was considering waiving the debt because its evaluation showed that the activities had been carried out in full and the cost of legal proceedings was likely to exceed the expected amount that could be recovered.

Note: the retention of supporting documentation is regulated in the contracts which transpose the provision of Article 132 of the Financial Regulation.

37 As explained in paragraph 35, the Commission’s corrective measures in the area of external actions are based on the financial impact of the irregular expenditure that had been retained after the adversarial procedures between the Commission and implementing organisations that take place after the hired auditors have issued their reports. We calculated from the data in our sample that DGs INTPA and NEAR reduced the irregular expenditure disclosed in final audit reports by an average of 35 % and 38 %, respectively, during their discussions with implementing organisations. There were many reasons for these reductions, such as implementing organisations providing supporting documentation that had not been given to or accepted as sufficient by the auditors (see example in Box 3). The Commission’s adversarial process would be more efficient if it were carried out together with the hired auditors, thereby eliminating the need to discuss and revise reported irregular expenditure at a later stage.

The Commission accepted most expenditure reported as irregular by the auditors after its own adversarial procedure

The external audit firm that verified the expenditure for an EU funded programme reported various cases of irregular expenditure. The largest was for staff costs that could not be substantiated because no time sheets were kept as evidence of the time charged to the programme. The international organisation that was managing the programme protested vigorously, complaining that considerable time had passed since the period that had been audited and that the auditor had not given it the opportunity to provide all the evidence. The Commission accepted some of the supporting documents that the implementing organisation later provided, and agreed that staff that had worked full time on the programme did not need timesheets. This resulted in the Commission reducing the amount to be recovered by 63Â % relative to its initial position.

38 The Financial Regulation states that when an authorising officer of the Commission establishes a recovery order, they should immediately send debit notes to the debtor, stating the amount due, the origins of the claim, the payment due date and the bank account number for the payment. If the debtor does not pay by the due dates, interest is charged on arrears12. The Commission’s Accounting Officer then sends the debtor at least one reminder, followed by a letter of formal notice, before initiating an enforced recovery. Once the due date has passed, the Accounting Officer may also call up any guarantees that the debtor may have lodged, or offset the debt against any outstanding amount(s) due to the debtor13.

39 We also reviewed a risk-based sample of 75 recovery orders that were open (unpaid) at the end of 2021 and included in the AARs of the four DGs that we selected for direct and indirect management, the aim being to assess the effectiveness of the Commission’s debt recovery process. The median times taken for the following stages of the debt recovery process are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7 – Delays in recovery procedures concerning a sample of recovery orders open at 31 December 2021

Source: ECA based on ABAC Data Warehouse.

40 A 2018 Commission decision on internal procedures states that the Commission should send reminders to debtors within 21 days of the deadline for receipt of the full payment expiring and that the letter of formal notice should be sent after another 21 days. Usually, the selected DGs did not comply with these deadlines. There is no delay set for requesting that the Commission’s Legal Service commence enforcement procedures. Our analysis reveals that the longest delays are in asking the Legal Service to start enforcement proceedings against the debtors after the Commission has sent them reminders and formal notices.

41 In its proposal to modify the recovery rules in the Financial Regulation14, the Commission acknowledged that its current recovery procedures are lengthier and more expensive when:

- debtors change their domicile without informing the Commission or the official registry;

- the Commission has to pay local lawyers and enforcement officers to follow up a case with different procedural steps in national courts; and

- debtors are insolvent and the Commission has to collect information to waive a claim.

42 We analysed data on recovery orders issued for irregular expenditure by the same four DGs between 2014 to 2022. The key debt recovery performance indicators are shown in Figure 8.

Figure 8 – At least 75 % of the total amount of the recovery orders issued were settled but after long delays, 2014-2022

Source: ECA based on ABAC Data Warehouse.

43 The data shows that external action DGs INTPA and NEAR have more difficulty recovering debts, as recovery rates are lower and the debts outstanding at the end of 2022 are higher than for Research DGs CONNECT and RTD. This may reflect the different environments in which external actions and internal policies operate. DG INTPA’s task of debt recovery is especially challenging because its directly managed operations involve implementing organisations located in 130 countries.

44 In 2022, DGÂ BUDG provided guidance15 for Commission departments on following up recoveries connected with investigations conducted by OLAF and EPPO, the aim being for them to recover more in less time. The document referred to the follow-up of financial recommendations that OLAF had issued between 2012 and 2020, noting that although DGs sought to recover around 50Â % of their total value, they actually only recovered 27Â %.

45 The same guidance urged authorising officers to establish amounts receivable and issue recovery orders without delay, as long as this did not interfere with OLAF and EPPO’s on-going investigations. It also provided for better monitoring and reporting on recoveries related to those investigations.

46 In 2024, after we completed our field work, DG BUDG proposed a new initiative to reduce the significant delays in the recovery process across the Commission16. The document stated that the recovery process does not always receive appropriate management attention and that it requires disproportionately high resources because of some cumbersome procedures. DG BUDG noted that debts totalling €450 million were overdue in October 2023. New measures proposed for direct and indirect management are:

- recovery performance standards to quantify the requirements of the Financial Regulation;

- compliance monitoring and reporting to compare performance;

- reinforced accountability, with corporate escalation mechanisms; and

- partial centralisation to achieve synergies and efficiencies by combining waiver decisions for recovery orders that involve the same debtors but are managed by different Commission departments.

Waivers are affected by delays in the recovery process and the solvency of debtors

47 The Financial Regulation allows the Commission to write off a debt by waiving all or part of the corresponding recovery order17. This is only possible in certain situations, such as where expected recovery costs exceed the amount being recovered, or where the debt cannot be recovered because of its age or the insolvency of the debtor.

48 The 2021 AARs of the four DGs show that the Commission waived €10 million during the year (2020: €8 million). We reviewed a sample of 52 of the 113 waivers that the four Commission DGs issued in 2021 in order to assess whether they had complied with the Commission’s recovery procedures and whether the reasons for writing the debts off were justified. The reasons for waivers are summarised in Figure 9.

Figure 9 – Reasons for waivers, 2021

Source: ECA based on ABAC Data Warehouse.

49 Based on our review of the documentation provided by the Commission, we found that it had sufficient justification for waiving the debts, and it had previously attempted to recover them. However, long delays in initiating enforcement procedures reduced the likelihood of recovering the debts. In addition, we note that the debtors were either financially weak or unwilling to accept the consequences of not complying with the requirements of the EU funding. The Commission had insufficient means of protecting the EU’s financial interests in these circumstances as it had no guarantees to call upon and no payments to offset the debts against (Box 4).

Debts written off due to enforcement challenges outside the EU

The Commission asked three non-EU NGOs located in the Asia Pacific region to repay the pre-financing they had received after they refused to comply with the requirements of their grant contracts. The NGOs refused to reimburse the funds received and the local lawyer hired by the Commission’s Legal Service not only estimated that the legal expenses would be high, but also believed that any legal action was unlikely to be successful. The fact was that the country in which the NGOs were located did not recognise European courts’ enforcement judgments and the NGOs had few assets. The three debts had to be written off.

The Commission monitors the member states’ systems for recording and recovering irregular expenditure under shared management, where such expenditure impacts the EU budget

50 When irregular expenditure is detected in the areas of agriculture and cohesion, EU and national law requires member states to recover undue payments (including penalties and interest, if applicable) from beneficiaries. We examined whether the Commission effectively monitors that member states ensure that irregular expenditure is correctly recorded and recovered without unnecessary delays.

The Commission monitors the member states’ recovery systems for agricultural funds as recoveries impact the EU budget

51 Agricultural funds are spent either through direct payments to EU farmers, market measures or through rural development programmes that are implemented by member states. The legal basis for the common agricultural policy (CAP) lays down a general requirement for national authorities to record irregular expenditure and to register the amounts owed in their debtors’ ledger within 18 months of being established18.

52 For direct payments and market measures (European Agricultural Guarantee Fund – EAGF), member states must reimburse any recoveries to the EU budget, after deducting an administration fee. The reimbursement involves deducting the recovery from expenditure declared to the Commission in the next monthly expense claim. In rural development (European Agricultural Fund for Rural Development – EAFRD), member states can re-use all amounts recovered from beneficiaries, but only within the same programme concerned. DG AGRI requires paying agencies to follow up the recovery of a debt within one year of the last event or action that is relevant according to the applicable national procedure. If a paying agency writes off a debt when it has taken all possible steps to recover irregular expenditure19, it can charge the amount to the EU budget. Otherwise, the national budget must bear the loss.

53 In our previous reports, we have already assessed the recovery of irregular payments under the CAP in 2004 and 201120:

- In 2004, we found a very low rate of recovery of irregular payments by the end of 2002 (a cumulative recovery rate of only 17Â % since 1971) and a large volume of old debts neither recovered nor written off. We also found that there are no clear criteria for deciding whether irrecoverable irregular payments should be charged to the member states or to the EU budget and we recommended the Commission to address it.

- In 2006, as a result of our recommendation, the 50/50 rule was introduced providing member states an incentive to recover debts faster. If recovery had not taken place within four years from the date of issuing of the recovery order, or within eight years where recovery is taken to the national courts, 50Â % of the financial consequences of the non- recovery had to be borne by the member state concerned and 50Â % by the EU budget, without prejudice to the requirement for the member state concerned to pursue recovery procedures21. The date on which the debt is recognised is therefore important for the application of the rule.

- In our 2011 audit, we concluded that member state systems to recover irregular expenditure have improved since 2004, with a recovery rate reaching around 50 % in respect of debts raised from 2006 onwards, also due to the 50/50 rule. Nevertheless, we highlighted that the rule also introduced a risk that member states “manage†the reporting and write-off process to their advantage, notably by delaying the date of debt recognition to avoid or postpone its application (and resultant charge to the national budget).

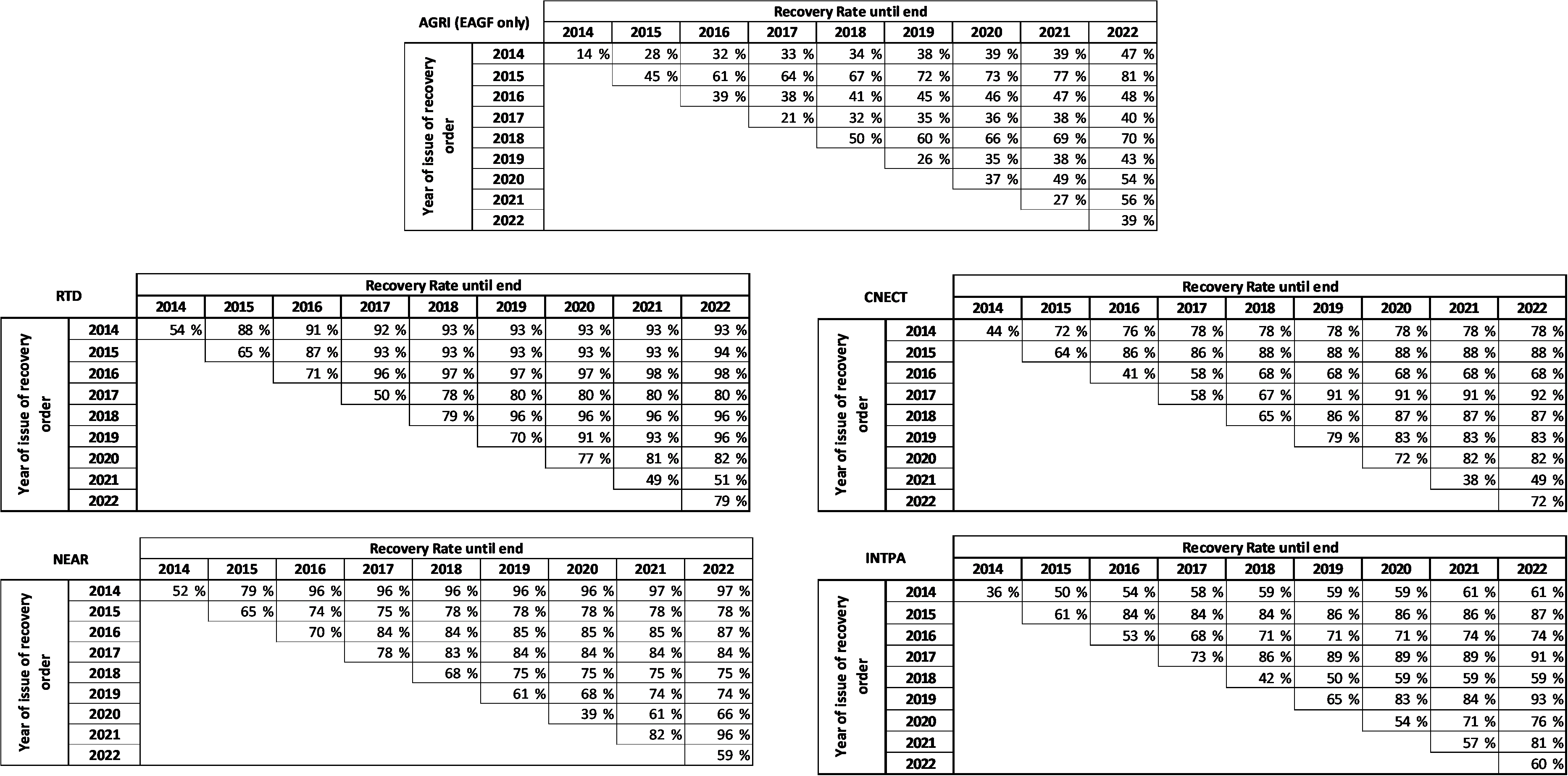

54 We analysed the data on recovery rates for the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund (EAGF) and the European Agricultural Rural Development Fund (EAFRD):

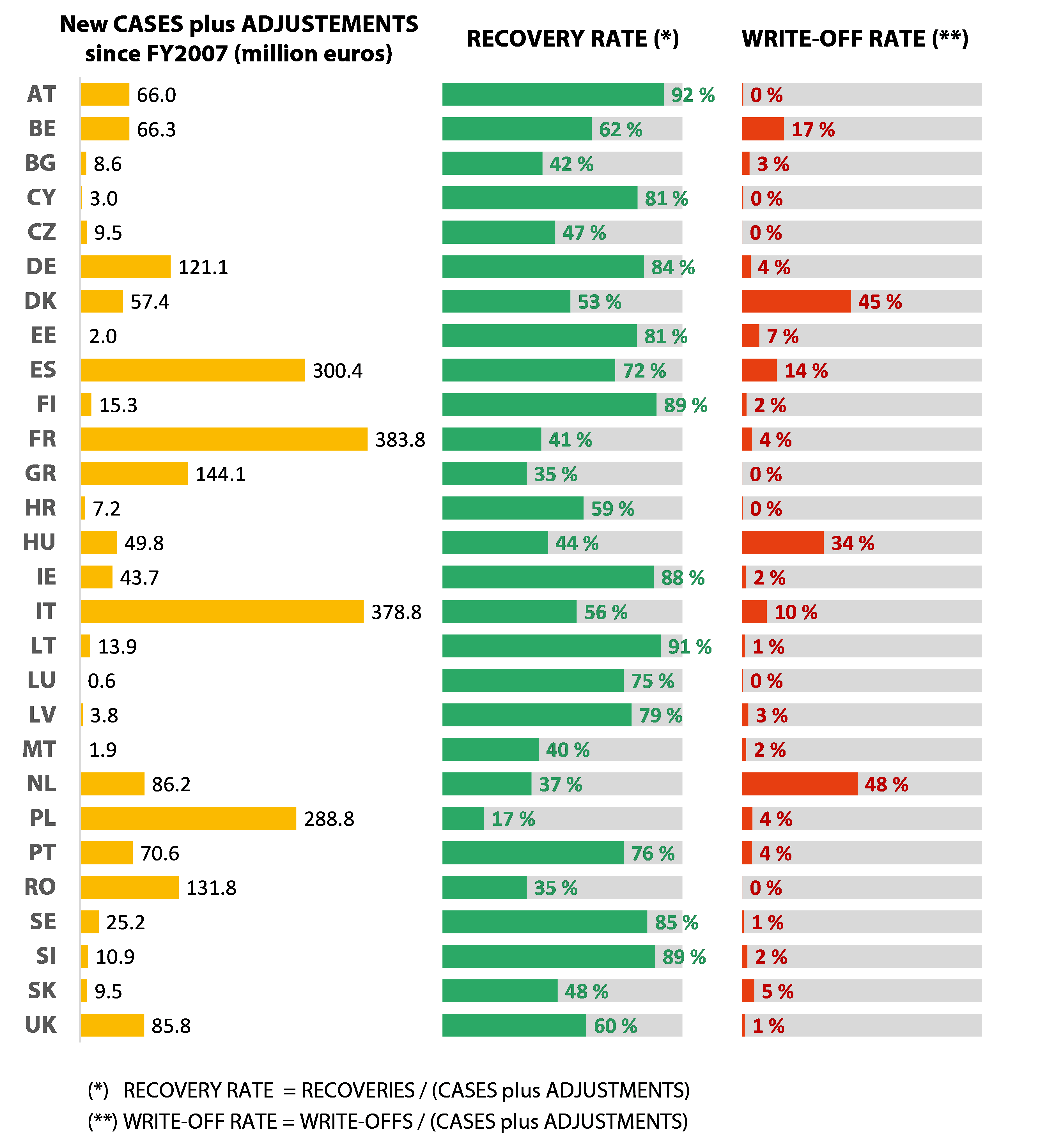

- For EAGF, the overall amount of irregular expenditure detected during the period 2007-2022 was €2.4 billion. 52 % was recovered by the end of 2022, whereas the remaining 48 % was either written off (9 %) or still outstanding (39 %)22. We noted significant differences in the rate of recovery and rate of write-off between member states, as shown in Annex V. Recovery rates varied between 17 % and 92 % while the rate of waivers varied between 0 % and 48 %.

- For EAFRD, DG AGRI does not present any recovery rates in its AAR. Based on the figures we received from DG AGRI, we established that the average recovery rate for the period 2015-2021 (where data was available) was 78Â %.

- When comparing the recovery rates between EAGF and EAFRD for similar periods (2015-2021), we note that the recovery rate for EAFRD, where member states can reuse funds recovered and national money is involved through co-financing, is significantly higher (78Â %) than for EAGF (49Â %).

- The recovery rates at beneficiary level for EAGF are generally lower than those for the programmes that we examined for direct and indirect management (Annex IV).

55 We also reviewed the results of DG AGRI’s monitoring of member state recovery systems for financial year 2021. DG AGRI and certification bodies identified weaknesses in recording and recovering irregular expenditure in 18 out of the 76 paying agencies. Weaknesses concerned the long delays (over 18 months) with which the paying agencies recorded irregular expenditure that they had detected, or weaknesses reported by certification bodies, such as failure to comply with the requirement to request recoveries from beneficiaries, or to follow up unpaid debts.

56 When member states do not address the weaknesses identified by certification bodies in the recovery systems, DG AGRI can apply financial corrections in the framework of the clearance of accounts or through the conformity clearance procedures, and applied financial corrections for a total of €513 million during the period 2010-2023. For most of the paying agencies with weaknesses in recoveries reported for financial year 2021, DG AGRI’s follow-up was still ongoing at the time of the audit. Box 5 provides an example of a follow-up action.

Financial correction applied by DGÂ AGRI for weaknesses in the recovery system of the Croatian paying agency

The certification body of Croatia identified cases where the paying agency initiated the recovery only after the 18 months deadline in the regulation. In the framework of the clearance of accounts procedure, DG AGRI asked Croatia for a thorough analysis of all debt cases. Consequently, the Croatian authorities confirmed a total of 411 cases affected by weaknesses in its recovery system (EAGF and EAFRD) with a total amount at risk of €0.8 million. DG AGRI applied a financial correction of the corresponding amount.

57 The 50/50 rule was not retained as part of the recovery management requirements introduced for the new CAP 2023-2027, and no alternative incentives were provided. We consider that without the 50/50 rule, which resulted in €234 million being repaid to the EU budget during the period 2015-2022, or an alternative incentive like those introduced for rural development (paragraph 54, 3rd bullet) or cohesion (paragraphs 58-63), there is the risk that the rate of recoveries at EU budget level in agriculture deteriorates.

In cohesion, the Commission does not monitor member states’ recovery systems because irregular expenditure is withdrawn and does not affect the EU budget

58 The control and assurance framework for cohesion spending was modified for the 2014-2020 programming period by requiring member states to submit annual assurance packages to the Commission, including certified accounts, which the Commission has to accept every year. This modification entailed changes in the way that member states follow up and correct irregular expenditure.

59 Managing authorities in the member states have to carry out checks before and after certified expenditure has been submitted to the Commission. If they find irregularities in expenditure reimbursed by the EU, but not yet submitted to the Commission in the annual accounts, they must record the irregular expenditure and withdraw it directly from the accounts. When irregularities are found in expenditure already submitted to the Commission, member states had the option to withdraw the expenditure right away in the next payment request, or to record it as pending recovery in the accounts and then withdraw the amount from EU expenditure once it has been recovered. In the 2021-2027 programming period, the latter option is no longer available and member states must withdraw irregular expenditure23.

60 Before national audit authorities submit certified accounts to the Commission, they check beneficiaries’ claims by selecting samples from the expenditure that was previously submitted to the Commission during the accounting year. Their audit work is summarised in the Annual Control Report. Any irregular expenditure detected should be recorded in the member state system.

61 The legal basis for cohesion requires member states to correct irregular expenditure and recover amounts unduly paid to beneficiaries, together with any interest24. Member states should take corrective measures within 12Â months of detecting irregular expenditure, and initiate the recovery procedure within the following 12Â months25. The Commission has issued guidelines to assist national authorities in recovering irregular expenditure from beneficiaries, in which it states that the recovery of irregular expenditure that has been withdrawn is a national issue26.

62 Certifying authorities in the member states are responsible for certifying the accounts. Certifying authorities must also report annually to the Commission on amounts that have been withdrawn, recovered, are yet to be recovered (pending recoveries), or cannot be recovered.

63 The Commission monitors the implementation of withdrawals as part of its desk review of annual assurance packages. Although the EU budget in the area of cohesion is generally protected as soon as irregular amounts have been withdrawn by member states, the Commission does not follow up whether member states recover the withdrawn irregular expenditure from beneficiaries. The recovery of irregular amounts is a key tool to deter beneficiaries from committing further irregularities and to minimise the reputational risks for the EU if beneficiaries of EU funded projects believe that corrective actions are ineffective.

The data that the Commission publishes on irregular expenditure are not always complete and consistent

64 The Commission publishes several reports containing data on irregular expenditure and subsequent actions to recover those amounts (paragraphs 15-18). We would expect the reports to provide stakeholders with complete and consistent data on irregular expenditure that has been detected in EU expenditure, and to state how it has been followed up and corrected in the interests of transparent and robust oversight.

Published data on irregular expenditure and corrective measures are not always complete

65 The data published for direct and indirect management are limited to preventive measures (ineligible expenditure excluded from cost claims) and corrective measures (recovery orders issued) that the Commission implemented during the year. The documents that the Commission publishes do not provide data for irregular expenditure that it detects during the year and records in its local audit databases. The Commission’s data on preventive and corrective measures are based on the year of implementation, not on when the irregular expenditure was detected. As Figure 6 shows, these time differences can vary, depending on the DG, up to three months. It is therefore not possible to obtain figures for the irregular expenditure detected during the year, or to establish how the Commission dealt with it.

66 In terms of shared management, neither DG AGRI’s AAR nor the AMPR provide an overall figure for irregular expenditure detected by checks and audits during the year for the CAP or for the corrective measures that resulted from them. The Commission does not provide an overall figure for irregular expenditure that has been recorded during the accounting year for cohesion. It takes the view that because member states withdraw irregular expenditure from their certified accounts, such expenditure is excluded from the EU’s accounts and does not have to be reported.

67 The AARs of the cohesion DGs provide data reported by member states for financial corrections that were implemented during the year following checks, audits and investigations. The figures for the 2020/2021 accounting year were €557.6 million for DG REGIO and €67.9 million for DG EMPL as at April 202227. In total, €625.5 million was detected and withdrawn from the expenditure submitted to the Commission to be co-funded by the EU. The Commission does not report what proportion of these amounts has been recovered from beneficiaries, as there is no impact on the EU’s accounts.

68 The only document that provides any data on irregular expenditure under shared management is the PIF report. The 2021 PIF report28 stated that member states reported a total of €30 million in fraudulent and €204 million in non-fraudulent irregular expenditure for agriculture through the Irregularity Management System. The corresponding figures for cohesion are €1 624 million and €812.9 million respectively. It should be noted that the PIF report only reports individual amounts over €10 000; in our previous reports, we found that the Commission had not carried out any systematic checks on the reliability of amounts reported by member states29.

Data on recoveries are not always consistent

69 We analysed the figures provided in different publications for recovery orders issued in 2021 for irregular expenditure by the four DGs that we examined during this audit for direct and indirect management. Table 2 provides an overview of the information that was published.

Table 2 – Information in published documents on recovery orders issued in 2021

| Figures extracted from published documents on recovery order issues in 2021 (million euros) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Document | DG INTPA | DG NEAR | Neighbourhood and the world * | External actions and pre-accession assistance | DG CONNECT | DG RTD | Single market, innovation and digital ** | Research and innovation |

Annual Activity Reports | 8.4 | 15.4 |

|

| 3 | 3.5 |

|

|

AMPR |

|

| 21 |

|

|

| 19 |

|

PIF report |

|

|

| 5.39 |

|

|

| 5.81 |

*This includes data for DGs ECHO, FPI, INTPA, NEAR and TRADE.

**This mainly includes data from DGs CONNECT and RTD and the ERCEA, INEA and REA executive agencies.

Source: the 2021 DG annual activity reports, the AMPR and the PIF report that were published in 2022.

70 We noted the following inconsistencies:

- the €23.8 million in the AARs of two of the external action DGs, INTPA and NEAR (€8.4 million and €15.4 million, respectively)30, exceed the overall figure shown in the AMPR for Neighbourhood and the world, which also includes DGs ECHO, FPI and TRADE. The Commission explained to us that the information presented in the AMPR included adjustments at consolidation level that were needed due to some limitations of the current accounting system and which in 2021 were not reflected in the AARs. The Commission has addressed this issue by manually including the adjustments in the AARs and harmonising the presentation of documents published for the 2022 accounting year; and

- the figures in the PIF report31 for total recoveries for the areas related to the four DGs are lower than the figures in the AMPR and AARs. The differences cannot be explained by the information provided in the PIF report.

71 We analysed the figures presented in the 2021 AMPR for agriculture (natural resources and environment) and found that preventive and corrective measures implemented by member states in 2021 totalled €794 million. This included corrective measures of €528 million before payment to beneficiaries during the year, which is consistent with DG AGRI’s AAR32. However, we also found that some figures published in the AMPR cannot be reconciled with those from the AAR because of timing differences in the data used33:

- the 2021 AMPR reported that €244 million in irregular expenditure was re-used by member states as a result of checks carried out on beneficiaries in 2021 and previous years. This figure cannot be reconciled with the information provided in DG AGRI’s AAR;

- corrective measures implemented by the Commission include “€191 million in corrections imposed on beneficiaries by the member states after payment and reimbursed to the EU budgetâ€34. Although this was reimbursed to the EU budget in 2021, the checks were carried out and requests for repayment issued in 2021 and previous years. The Commission explained to us that the figure mostly consists of €112.7 million for the European Agricultural Guarantee Fund, which is confirmed by the DG’s AAR35, and €68.6 million for rural development projects, which was included in the Commission’s financial accounts and is not shown in the AAR.

72 For cohesion, the AMPR discloses that member states implemented €3 763 million of preventive and corrective measures in 202136, a figure which includes the financial corrections mentioned in paragraph 67. This is the EU share of the withdrawals and deductions that member states made from expenditure declared to the Commission. This figure does not correspond to the €3 204 million and €838 million in the 2021 AARs of the cohesion DGs REGIO and EMPL, because national co-financing is included37. This issue was rectified in the 2022 AARs, in which the EU share is shown.

Conclusions and recommendations

73 We conclude that the Commission’s systems for managing and monitoring irregular expenditure incurred by beneficiaries of EU funds are partially effective. While the Commission ensures the accurate and prompt recording of irregular expenditure, it takes too long to recover it under both direct and indirect management. Regarding shared management, the significant share of unrecovered irregularities in agriculture and the fact that recovery rates have not improved since 2006 indicates that the Commission’s monitoring might not be on its own sufficient to ensure the effective performance of the member states recovery systems. In cohesion, when irregular expenditure is withdrawn from payment claims, the EU budget is protected and the Commission does not follow up whether these amounts are subsequently recovered from beneficiaries. Furthermore, the information that the Commission provides on irregular expenditure and subsequent corrective measures is of limited use, as it is not always complete and consistent.

74 Our checks of a sample of audits and verifications of directly and indirectly managed operations showed that the Commission recorded irregular expenditure in a correct and timely manner (paragraphs 26-28). However, we observed that in the case of external actions, the full financial impact of systemic irregular expenditure is not recorded in the Commission’s management systems. This is because auditors are not contractually required to carry out additional checks on irregular expenditure that may be systemic in nature and the Commission does not ensure that systemic irregular expenditure does not affect other grants that the same implementing organisations have received (paragraph 30). The risk of unreported systemic irregular expenditure is especially high in the case of UN agencies due to limitations in the scope of verifications (paragraph 31).

Recommendation 1 – Examine the financial impact of systemic irregular expenditure in the area of external actions

The Commission should ensure that the full financial impact of irregular expenditure that may be systemic in nature is determined, recorded and corrected, if necessary, by carrying out additional checks of the EU funded operations concerned.

Target implementation date: June 2026

75 We found that it typically took 14 to 23 months between implementing organisations carrying out EU funded activities and the Commission issuing recovery orders. The time spent on adversarial procedures in the area of external action is usually five to nine months longer than for internal policies. Even if the inherent differences between the two types of management are acknowledged, we consider that the level of monitoring and supervision provided by the Common Audit Service in the area of research helps to reduce the time needed to detect and correct irregular expenditure (paragraphs 33-37).

76 We also found that, for unpaid recovery orders, the Commission services typically take between 5 and 8 additional months to initiate the enforcement process to recover funds (paragraphs 38-43). The delays in recovering irregular expenditure reduce the Commission’s chances of being able to recover the total amounts owed, especially when the implementing organisations are unable or unwilling to repay their debts (paragraphs 48 and 49). DG BUDG has recently tried to address the delays in the Commission’s recovery process (paragraphs 44-46). Once fully implemented, this may have the potential to address delays in enforcement procedures when debtors do not repay EU funds after the Commission has issued a final or formal notice.

Recommendation 2 – Improve the planning of audit work in the area of external actions to reduce the time taken to establish irregular expenditure

The Commission should reduce the time taken in the area of external actions between the completion of the activities funded by the EU and the establishment of irregular expenditure to be corrected by:

- reviewing its audit planning methodology so that ex post checks are carried out as soon as it receives compliant financial reports; and

- using monitoring procedures and tools that will allow for closer follow-up of the audit process so as to reduce the length of adversarial procedures.

Target implementation date: end of 2025

77 Under shared management, member states have primary responsibility for recording and recovering irregular expenditure. In agriculture, where the Commission monitors the member states’ systems, 48 % of the €2.4 billion recoveries for direct payments and market measures that paying agencies had issued and not cancelled since 2007 were irrecoverable or still outstanding at the end of 2022. Furthermore, the recovery rates at beneficiary level for EAGF are generally lower than for direct and indirect management. The 50/50 rule that was meant to encourage paying agencies to recover debts in a timely manner no longer applies in the 2023-2027 common agricultural policy. Without an incentive to recover there is the risk that the rate of recoveries in agriculture deteriorates (paragraphs 51-57).

Recommendation 3 – Assess the need for additional incentives for member states to improve the rates of recovery of irregular expenditure in agriculture

In order to ensure that member states recover irregular expenditure under the CAP in a more timely manner, and improve the recovery rates, the Commission should assess the need to include additional incentives in the next programming period.

Target implementation date: end of 2025

78 In the area of cohesion, member states correct irregular expenditure by withdrawing it from certified expenditure immediately after it has been detected. This means that the EU budget is protected as soon as irregular expenditure has been detected and withdrawn. The Commission does not follow up whether member states recover the withdrawn irregular expenditure from beneficiaries. The recovery of irregular amounts is a key tool to deter beneficiaries from committing further irregularities and to minimise the reputational risks for the EU (paragraphs 59-63).

79 We found that the information that the Commission publishes on irregular expenditure, recoveries and other corrective measures is not always complete and consistent. None of the documents that the Commission publishes provide a complete overview of the established irregular expenditure and the link to the corrective measures taken (paragraphs 65-72).

Recommendation 4 – Provide complete information on established irregular expenditure and corrective measures taken

The Commission should provide data in its annual activity reports on:

- irregular expenditure that has been established during the year and the corrective measures that have been taken; and

- irregular expenditure that was established during the previous year(s) but for which corrective measures were not finalised at the end of the previous year, and the corrective measures that have been taken the current reporting year.

Target implementation date: June 2026

This report was adopted by Chamber V, headed by Mr Jan Gregor, Member of the Court of Auditors, in Luxembourg at its meeting of 22 March 2024.

For the Court of Auditors

Tony Murphy

President

Annexes

Annex I – Systems for detecting, recording and reporting irregular expenditure, and corrective measures for selected EU programmes

Natural resources (agriculture)

Paying agencies carry out administrative checks on all beneficiaries, as well as on-the-spot checks, and sending statistics to DGÂ AGRI by 15Â July every year. The coverage rate of on-the-spot checks is typically 5Â % but this varies by measure.

Certification bodies check and certify the paying agencies’ annual accounts, their internal control procedures, recovery systems, and the legality and regularity of the expenditure that the EU reimburses. They also re-perform samples of on-the-spot checks carried out by each paying agency. Paying agencies submit their annual accounts and certification reports to DG AGRI by 15 February every year for clearance.

In the event of irregular expenditure or negligence, member states must request the recovery from beneficiaries of undue payments (including penalties, if applicable) within 18 months of the approval or receipt of an inspection report38. When the recovery request is made, paying agencies should register the amounts owed in their debtors’ ledger, and follow up the recovery of the debt within one year of the last event or action that is relevant, based on national procedure39.

Member states can re-use all amounts recovered for rural development programmes, but they must reimburse any recoveries for direct payments and market measures to the EU budget as assigned revenue, after deducting a 20Â % administration fee (25Â % for cross-compliance). The reimbursement involves deducting the recovery - including penalties and interest - from the next monthly expense claim.

Paying agencies can offset recoveries for direct payments against future payments to the same beneficiary. However, they cannot do so in the case of recoveries of EU funds for market measures (under the EAGF) and completed rural development activities with no further payments due.

If a paying agency writes off a debt after exhaustive recovery efforts, it can charge that debt to the EU budget in the next expenditure declaration, failing which the national budget must bear the loss. Until 2022, paying agencies applied the 50/50 provision if they could not recover a debt within four years (eight years if judicial proceedings are involved), meaning that the cost was shared equally between the EU and national budgets. After applying this mechanism, paying agencies had to continue with their recovery procedures, otherwise they had to bear the full loss themselves, and record the outcomes in their next annual accounts.

DG AGRI carries out limited on-the-spot checks for its annual financial clearance of accounts and multi-annual conformity audit visits. The financial clearance covers the completeness, accuracy and veracity of the paying agencies’ accounts, whereas the conformity audits - of which it carried out 92 in 2022 - are designed to exclude expenditure that was not incurred in line with the rules. If the Commission detects irregular expenditure, paying agencies must request reimbursement from final beneficiaries and then return the recovered amounts to the EU budget40.

Cohesion

Managing authorities perform administrative checks on all payment claims and on-the-spot verifications of samples of payment claims received from beneficiaries. Any ineligible amounts they detect are deducted from the amounts to be reimbursed to them, or they request recoveries if the amounts to be paid to beneficiaries are insufficient. The Commission does not require managing authorities to report data on ineligible amounts.

If managing authorities find irregular expenditure that has already been declared to the Commission, they deduct the irregular amount, as it is ineligible for co-financing and should not be included in the expenditure declared to the Commission. Managing authorities have two options for adjusting the eligible expenditure reported to the Commission:

- they may show these amounts as withdrawals of eligible expenditure. In this case, they can re-use the EU funding for the same operational programme from which it was withdrawn; or

- they may leave irregular expenditure in the operational programmes until they recover it from the beneficiary. This option has a cash-flow advantage but gives the managing authorities less time to re-use the funds when they have been recovered. This option was used by only five member states during the 2014-2020 programming period and no longer exists in the current period.

Certifying authorities are responsible for certifying the final accounts submitted to the Commission. They consolidate the “corrected†figures provided by the managing authorities and apply any other corrections that have to be made to accounts following the checks carried out by the audit authorities, the Commission or the European Court of Auditors. In addition, certifying authorities perform their own checks, which may result in expenditure being considered as high risk and being classified as subject to “on-going assessmentâ€. Although part of the accounts, this type of expenditure must be reported separately and is not considered for co-financing by the Commission. Once further checks have been carried out, these amounts can be partly or entirely reintroduced in subsequent payment claims.

Before the managing authorities submit the annual accounts to the Commission, audit authorities also check beneficiary claims by selecting samples from the expenditure in the payment claims that the managing authorities submitted to the Commission during the accounting year. Their audit work is summarised in the Annual Control Report. Irregular expenditure detected in audits of operations is corrected in the accounts. If their work results in a Total Error Rate (TER) above 2Â %, they are obliged to make additional extrapolated financial corrections in order to bring the residual risk below the 2Â % materiality threshold.

The annual assurance package that member states submit to the Commission contain the accounts of operational programmes that have been approved for the programming period, the audit authorities’ annual control reports, their audit opinions, annual summaries and the management authorities’ declarations. The Commission carries out desk reviews of these documents.

The Commission also carries out audits of national authorities that are selected by means of risk analyses. These audits have different objectives, such as compliance, fact-finding, thematic, systems and the reliability of performance indications, and may involve re-performing the checks carried out by the member state audit authorities. Such audits mostly lead to financial corrections that usually result in the national authorities re-using the amounts for their programmes. Member states are responsible for taking corrective action in respect of beneficiaries for any irregular expenditure that has been detected.

Internal and external policies

The Commission usually hires private audit firms to check the eligibility of expenditure reported by implementing organisations for project contracts or agreements that the Commission manages directly or indirectly. These checks may be carried out as part of the annual audit plans with projects selected by risk analysis, or as part of the measurement of the residual error rate for projects selected randomly. Some contracts or agreements may require implementing organisations to hire private audit firms to audit the financial accounts that they submit to the Commission.

The research DGs have set up a Common Audit Service (CAS) to hire private audit firms on the basis of a framework contract agreement or carry out audits using its own staff. If private audit firms carry out audits, a CAS representative closely monitors them. CAS and the hired auditors discuss the findings with auditees during an adversarial procedure before the hired auditors issue their final audit reports. CAS records the full impact of the irregular expenditure in the AUDEX audit management database, which automatically transfers the data to the SyGMa grant management system, so that authorising officers can carry out a further short adversarial procedure, sending the audit reports to the implementing organisations before taking corrective measures regarding the irregular expenditure that has been reported.

The external actions DGs have also set up a framework hiring agreement for private audit firms. Audit Task Managers work with authorising officers to hire the auditors and co-ordinate their work, approving draft audit reports before they are submitted as final. Authorising officers then send the final audit reports to implementing organisations, which may then comment on any irregular expenditure detected and provide additional supporting documentation. At the end of this adversarial procedure, authorising officers decide upon the corrective measures to be taken for the irregular expenditure that they have confirmed.

In the area of external actions, the Commission manages some expenditure indirectly with implementing partners, such as international organisations and public law bodies that are financially guaranteed by member states. The Commission relies on their management systems to detect and recover irregular expenditure incurred by beneficiaries. The Commission has established pillar-assessment methodology41 to ensure that its implementing partners provide an equivalent level of protection for the EU’s financial interests as the Commission provides for direct management.

The Commission and the United Nations have established a Financial and Administrative Framework Agreement with a view to working together. The Common Understanding on the use of the terms of reference for expenditure verifications limits the samples that verifiers can select to check the eligibility of an operation that a UN agency has managed with EU funds42. Samples cannot exceed 40 transactions from an agency’s primary transaction listing, and 20 % of reported expenditure. If the list includes transactions with implementing partners that require sub-level sampling, a maximum of 20 additional items may be selected for up to five of the sampled transactions. Lastly, expenditure verifiers are not allowed to keep copies of supporting documents that they have checked.

Authorising officers at the Commission correct irregular expenditure by means of recoveries or lower subsequent payments. The Commission treats recovered funds as assigned revenue.

Authorising officers are responsible for drawing up estimates of amounts receivable, establishing entitlements to be recovered, recording them in ABAC, and issuing recovery orders and debit notes. Before the approval process is completed in ABAC, the Commission’s Accounting Officer examines recovery orders to ensure that all the necessary requirements are fulfilled and that the steps needed to ensure an effective recovery procedure have been taken.

If a debtor has not paid by the deadline stipulated in the debit note, the recovery order is assigned in DG BUDG’s debt recovery (dunning) team. If the debtor still does not pay the debt after being sent a reminder and formal notice, and there is no possibility for offsetting or clearing via a bank guarantee, the Accounting Officer invites the authorising officer to proceed with enforced recovery. The authorising officer does this by sending a request accompanied by supporting documentation to the Commission’s Legal Service. This may be executed on the assets of the debtor: either via the adoption of a Commission Decision (Article 299 TFEU) or by means of judicial proceedings.

Authorising officers may waive debts in the following cases43:

- where the foreseeable cost of recovery would exceed the amount to be recovered and the waiver would not harm the image of the EU;

- where the amount receivable cannot be recovered in view of its age, the delay in sending the debit note, or the insolvency of the debtor; and

- where recovery is inconsistent with the principle of proportionality.

Annex II – European Commission systems for detecting irregular expenditure and carrying out corrective measures under direct and indirect management

Source: ECA.

Annex III – Member states’ systems for detecting irregular expenditure and carrying out corrective measures under shared management

Source: ECA.

Annex IV – Recovery rates of irregular expenditure for selected Commission Directorates-General

Note: The recovery rates do not take into account amounts offset against payments to the beneficiary during the same claim year for EAGF or project for direct and indirect management.

Source: Table: Annex 7-5.4-1 for the EAGF on p. 238 of the Annual activity report 2022 - Agriculture and Rural Development - annexes and ECA based on ABAC.

Annex V – European Agricultural Guarantee Fund recoveries from beneficiaries for cases detected since 2007

Source: Table: Annex 7-5.4-1 for the EAGF on pp. 238-239 of the Annual activity report 2022 - Agriculture and Rural Development - annexes.

Abbreviations

AAR: Annual activity report

AMPR: Annual management and performance report

CAP: Common Agricultural Policy

CAS: Common Audit Service

DAC: Joint Audit Directorate for cohesion of DGs EMPL and REGIO

DGÂ AGRI: Directorate-General for Agriculture and Rural Development

DGÂ BUDG: Directorate-General for Budget

DGÂ CONNECT: Directorate-General for Communications Networks, Content and Technology

DGÂ EMPL: Directorate-General for Employment, Social Affairs and Inclusion

DGÂ INTPA: Directorate-General for International Partnerships

DGÂ MARE: Directorate-General for Maritime Affairs and Fisheries

DGÂ NEAR: Directorate-General for Neighbourhood and Enlargement Negotiations

DGÂ REGIO: Directorate-General for Regional and Urban Policy

DGÂ RTD: Directorate-General for Research and Innovation

FAFA: Financial and Administrative Framework Agreement

IMS: Irregularity Management System

OLAF: European Anti-Fraud Office

Glossary

ABAC: The Commission’s electronic system for managing its budgetary and accounting operations.

Adversarial: Procedure in which the auditor and/or Commission discusses the results of its control checks with the auditee to ensure they are well founded.

Annual management and performance report: Report produced every year by the Commission on its management of the EU budget and the results achieved, summarising the information in the annual activity reports of its directorates-general and executive agencies.

Annual activity report: Report produced by each Commission directorate-general and EU institution or body, setting out how it has performed in relation to its objectives, and how it has used its financial and human resources.

Cohesion: The EU policy which aims to reduce economic and social disparities between regions and member states by promoting job creation, business competitiveness, economic growth, sustainable development, and cross-border and interregional cooperation.

Direct management: Management of an EU fund or programme by the Commission alone, in contrast to shared management or indirect management.

Financial and Administrative Framework Agreement: Agreement between the Commission and the UN governing cooperation between them on the Millennium Development Goals.

Indirect management: Method of implementing the EU budget whereby the Commission entrusts implementation tasks to other entities (such as non-EU countries and international organisations).

Irregularity Management System: Application that member states use to report irregularities, including suspected fraud, to OLAF.

Shared management: Method of spending the EU budget in which, in contrast to direct management, the Commission delegates to member states while retaining ultimate responsibility.

Audit team

The ECA’s special reports set out the results of its audits of EU policies and programmes, or of management-related topics from specific budgetary areas. The ECA selects and designs these audit tasks to be of maximum impact by considering the risks to performance or compliance, the level of income or spending involved, forthcoming developments and political and public interest.

This performance audit was carried out by Audit Chamber V Financing and administration of the EU, headed by ECA Member Jan Gregor. The audit was led by ECA Member Jorg Kristijan PetroviÄ, supported by Martin Puc, Head of Private Office and Mirko Iaconisi, Private Office Attaché; Judit Oroszki, Principal Manager; Anthony Balbi, Head of Task; Bruno Scheckenbach and Ilias Nikolakopoulou, Auditors. Jesús Nieto Muñoz, graphic designer; and Valérie Tempez provided the secretarial assistance.

From left to right: Mirko Iaconisi, Judit Oroszki, Jorg Kristijan PetroviÄ, Anthony Balbi, Martin Puc.

COPYRIGHT

© European Union, 2024

The reuse policy of the European Court of Auditors (ECA) is set out in ECA Decision No 6-2019 on the open data policy and the reuse of documents.

Unless otherwise indicated (e.g. in individual copyright notices), ECA content owned by the EU is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International (CCÂ BYÂ 4.0) licence. As a general rule, therefore, reuse is authorised provided appropriate credit is given and any changes are indicated. Those reusing ECA content must not distort the original meaning or message. The ECA shall not be liable for any consequences of reuse.

Additional permission must be obtained if specific content depicts identifiable private individuals, e.g. in pictures of ECA staff, or includes third-party works.

Where such permission is obtained, it shall cancel and replace the above-mentioned general permission and shall clearly state any restrictions on use.

To use or reproduce content that is not owned by the EU, it may be necessary to seek permission directly from the copyright holders.

Figures 4, 6 and 7 – Icons: These figures have been designed using resources from Flaticon.com. © Freepik Company S.L. All rights reserved.

Software or documents covered by industrial property rights, such as patents, trademarks, registered designs, logos and names, are excluded from the ECA’s reuse policy.

The European Union’s family of institutional websites, within the europa.eu domain, provides links to third-party sites. Since the ECA has no control over these, you are encouraged to review their privacy and copyright policies.

Use of the ECA logo

The ECA logo must not be used without the ECA’s prior consent.

| ISBN 978-92-849-2052-5 | ISSN 1977-5679 | doi:10.2865/089 | QJ-AB-24-007-EN-N | |